Matthew Carey Salyer and Anne Halloin, students in Dr. Susanne Hafner’s summer 2023 graduate class MVST 5311: Arthurian Literature, weigh in on this year’s Broadway revival of Lerner & Lowe’s beloved musical Camelot:

The odds were on Aaron Sorkin’s revival of Lerner and Loewe’s classic musical, Camelot, being a long-running success. It boasted a new script, updated for contemporary New York theatergoers by the popular West Wing writer-director. The production reunited Sorkin with Bartlett Sher, his creative partner from 2018’s Broadway hit, To Kill a Mockingbird. The venue, Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, provided one of the more intimate settings for a New York production of Camelot’s scale, somehow still managing to accommodate a thirty-piece orchestra that made Alan Jay Lerner’s librettos seem like living characters of their own. With all of this effort and expense, it was no surprise that Sorkin’s Camelot received five Tony nominations, including Best Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role, Best Scenic Design, Best Costume Design, and Best Revival of a Musical. The surprise came when Camelot won none of them. In fact, in what can only be considered a shocking failure, Camelot closed months earlier than expected after only 115 performances. In one sense, Sorkin’s production mirrored its source, what Tennyson called in part King Arthur’s “city built to music, therefore never built at all” in his Idylls of the King. But why did this Camelot, so well-funded and well-produced, and with such popular music, fail so royally on Broadway?

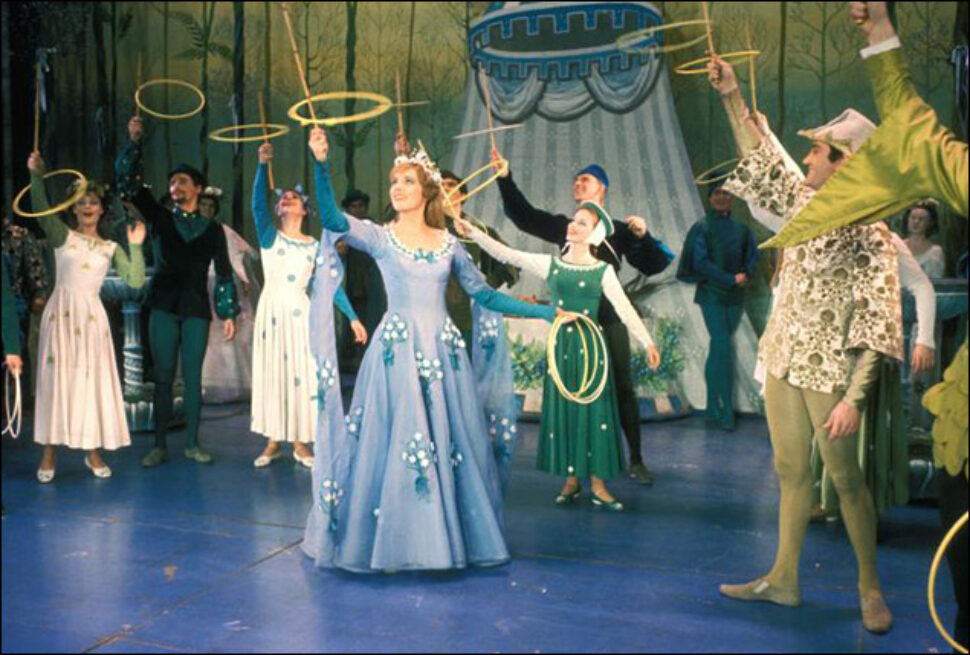

Both Lerner and Loewe’s original and Sorkin’s rewrite faced numerous production challenges. Lerner and Lowe’s 1960 Camelot, which drew its inspiration from T.H. White’s voluminous, sprawling The Once and Future King – a series of four novels based on Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur – premiered on Broadway with an excruciating runtime of more than four hours. Noel Coward, for example, was reported to have quipped that the musical was “as long as the Götterdämmerung and not nearly as funny!” The production team struggled to make needed edits, hampered by Lerner’s hospitalization, Lowe’s diverging vision for the musical, and Moss Hart’s heart attack, which forced Lowe to step in as acting director. By most accounts, Camelot was salvaged by the popularity of its music and magical spectacle, as well as the charismatic rapport and enthusiasm of its stars: Richard Burton, Julie Andrews, and Robert Goulet. Being featured on the Ed Sullivan Show and later embraced by the Kennedy administration firmly cemented Lerner and Loewe’s musical as an iconic Broadway fixture for its era.

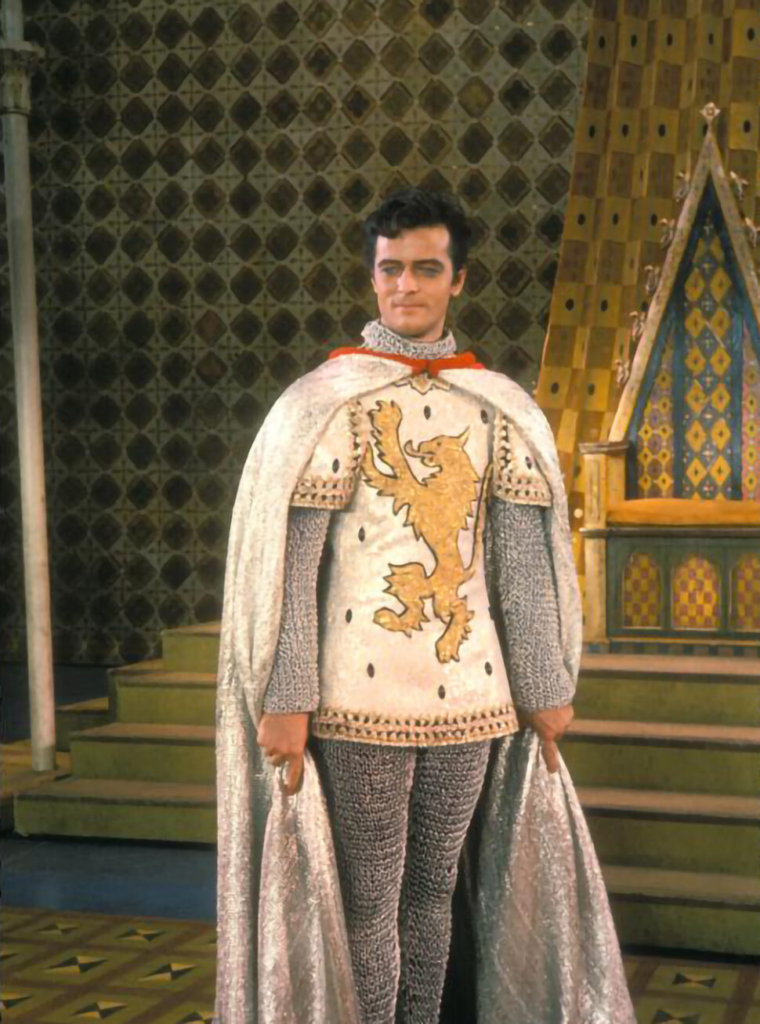

However, the challenges faced by the original writers had never truly been resolved, and many agreed that a modern revival should attempt the project yet again. During Sorkin’s process of updating and streamlining the musical’s book, he was impeded by a serious stroke that left him unable to write his name. His hope that Camelot would “make you feel two inches taller than when you came into the theater” seems to speak to the production as a personal as well as imaginative struggle. As with Lerner and Loewe’s original, most of that experience – Camelot as uplifting, transfixing, theatrical transport – fell to the phenomenally talented cast, including Philipa Soo as the tempestuous Queen Guinevere, Jordan Donica as the dreamy, daring, and slightly tongue-in-cheek Sir Lancelot, and Andrew Burnap as the idealistic, self-doubting King Arthur. Burnap, in particular, filled the familiar role of “Sorkin” hero – a sort of younger, armored version of Jeff Daniels’s Will McAvoy from The Newsroom. His repartee with Soo’s quicker, savvier Guinevere was staged, for better or worse, with The West Wing’s “walk-and-talk” semi-sardonic tempo. In lieu of West Wing camera movement, Camelot’s smarter-than-thou royal politicos managed to enchant, at turns, through B.H. Barry’s turbulent, choreographed swordplay and Kimberly Grigsby conducting sweeping movements of the Beaumont Theater’s phenomenal orchestra.

Lincoln Center’s Camelot displayed all sorts of compelling stagecraft, turns of phrase, and fine performance, but these cosmetic upgrades to the original musical failed to spark theatrical magic. Much of the blame lies with Sorkin’s rewrite: its hyper-rational and self-effacing attitude conveyed a tone of embarrassment of its source material. In a recent interview with former presidential speechwriter, Jon Favreau, Sorkin described his ideal, relatable protagonist as “a guy who does his job completely but not well, a guy who’s very likable but there is something stopping him from doing something very great.” In Washington D.C. terms, he is a bit of a policy wonk, someone who gets unusually excited about collecting the coasters with political caricatures from the basement bar at the Hay-Adams.

One of Sorkin’s most deliberate changes to Camelot’s book involved reassigning songs and rewriting dialogue to reflect shifts in gender roles since the musical’s 1960 premiere. At least until Camelot’s tragic fall, King Arthur and Queen Guinevere are self-described “business partners,” with Guinevere the intellectual senior partner of the pair. For Sorkin, this reassessment of Camelot’s gender politics goes hand-in-hand with a wholesale rejection of magical elements in the King Arthur source material. This extends so thoroughly to the “magical” elements of Lerner and Loewe’s production – staging, costuming, sentimental songs – that one wonders who Sorkin imagined as his audience. In lieu of magic, science becomes its substitute, with the Enlightenment threatening to bring its technological advancement and destroy the world that Camelot inhabits (not that Sorkin pays too much attention to precise dating; this thousand year stretch of history seems all the same to him). “The Middle Ages won’t end themselves,” Arthur remarks with a wink. There are analogies to be made between the arbitrariness of magic spells and the sorts of social ideologies and hollowed-out traditions that Camelot’s Arthur and Guinevere subvert or deride. But this also renders them characters who can do little in the way of growing, resisting, or defining themselves as dramatic individuals within the world they occupy. They simply know more than Camelot, singing its music with winks, nudges, and scripted distaste.

Nostalgia is its own species of magic. During the 1960’s, Camelot became part of the iconographies surrounding the Kennedy administration and America’s cultural mood of lost innocence. After the JFK assassination in 1963, its elegiac tone assumed new resonance, in no small part due to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Arthurian writer, T.H. White, who made the analogue overt. But this elegiac nostalgia drew lasting power, in spite of the original production’s unwieldiness, from Lerner’s tight, lighthearted score paired with Loewe’s witty, urbane, hopeful, and sometimes endearingly naïve dialogue. The original book, styled after the success of My Fair Lady, winked at the traditions of a bygone era while simultaneously respecting and evoking it. In Camelot’s case, sheer spectacle amplified this. Perhaps its greatest unsung triumph was Tony Duquette’s original set design, lavishly outfitted with eye-popping technicolor silk, which evoked a distant, impossibly perfect place where “the rain may never fall till after sundown.” Of course, when that line in Camelot’s eponymous song occurs, Sorkin makes sure to let us know that his characters know that rain does not work like that. What Sorkin failed to realize in his rewrite was that the magic, the mystery, and the escape from modernity were what distinguished Camelot from a civics lecture.

That is, in essence, what Sorkin’s rewrite became. Removing the magic from the Arthurian mythology left nothing to the plot but a forced love triangle and a bitter, rambling political diatribe. The balance of the original book was that while it allowed audiences to chuckle at outdated tradition. In contrast, the revised script openly ridiculed its source material. The song King Arthur sings to Guinevere about the appeal of Camelot, indeed the title number from the show, was regularly referred to later in the show as “that stupid song about the weather.” When Lancelot revives Arthur from his seemingly fatal blow, the gathered crowd regards the act as a miracle; Arthur ridicules everyone surrounding him, “I wasn’t actually dead!”Arthur continually complains about the abysmal educational standards of his kingdom, and that his subjects were gullible enough to believe in dragons, of all things. The dialogue, in an attempt to replicate witty repartee, often came across as mean-spirited and nasty. Through the mouthpiece of King Arthur, Sorkin endlessly complains about the superstitious stupidity of the Middle Ages where Camelot is set–and, essentially, of the audience, too, if they enjoyed the musical in its original form.

Despite the no-expenses-spared ethos–which included a thirty piece orchestra and twenty-seven member cast–the entire show felt remarkably bare-boned. The stage design left the set almost completely empty, save for a few partitions, and, in an attempt at realism, left the fake stone without color, tapestries, or any sort of adornment. The set felt far too large for the actors, who could not fill the space by themselves. The set design imitated the script, which tore away the magic and spectacle, leaving only a spirit of modern stoicism that felt chilling and hostile to the imagination.

The entire production felt as though Sorkin were forcing the world of Camelot into the West Wing. The Middle Ages could be ‘solved’, in Sorkin’s opinion, with the application of reason, democracy, and common sense. Emphasizing King Arthur’s political strategies in creating his kingdom is nothing new, and T.H. White certainly reinterpreted the Arthurian legend for a modern political landscape, with Merlyn instructing the young King on the dangers of authoritarianism. The legend of King Arthur easily lends itself to political analysis and idealism: the round table, which emphasized the equality of its knights, can be interpreted as a kind of proto-democratic structure. However, the community and the camaraderie of these knights banding together to make a better world failed to appear in Sorkin’s rewrite. Instead of reigning over a round table, Arthur sits at a square chessboard, often alone, complaining about his knights who are unable to grasp the genius of his democracy. Ironically, in his effort to bring progress to the Middle Ages, Arthur alone attempts to impose a system of government upon Camelot which feels unwanted and then resented by his subjects. These snide remarks and assurances of his superior intelligence did little to make King Arthur “a guy who’s very likable,” as Sorkin originally imagined him. The plot crescendos towards a close as the barbaric knights storm the gates, Guinevere and Lancelot fall into bed together, and a war breaks out amidst the chaos. Ultimately, no one in the audience seemed especially grieved when the plot of Camelot sped towards its tragic failure.

Photos from Playbill.com